A Close-look at RAG System Optimization

Table of Contents

An Introduction to RAG

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) is a new paradigm in building large language models (LLM) agents. It improves the accuracy and reliability of generative AI applications by leveraging the facts fetched from external sources.

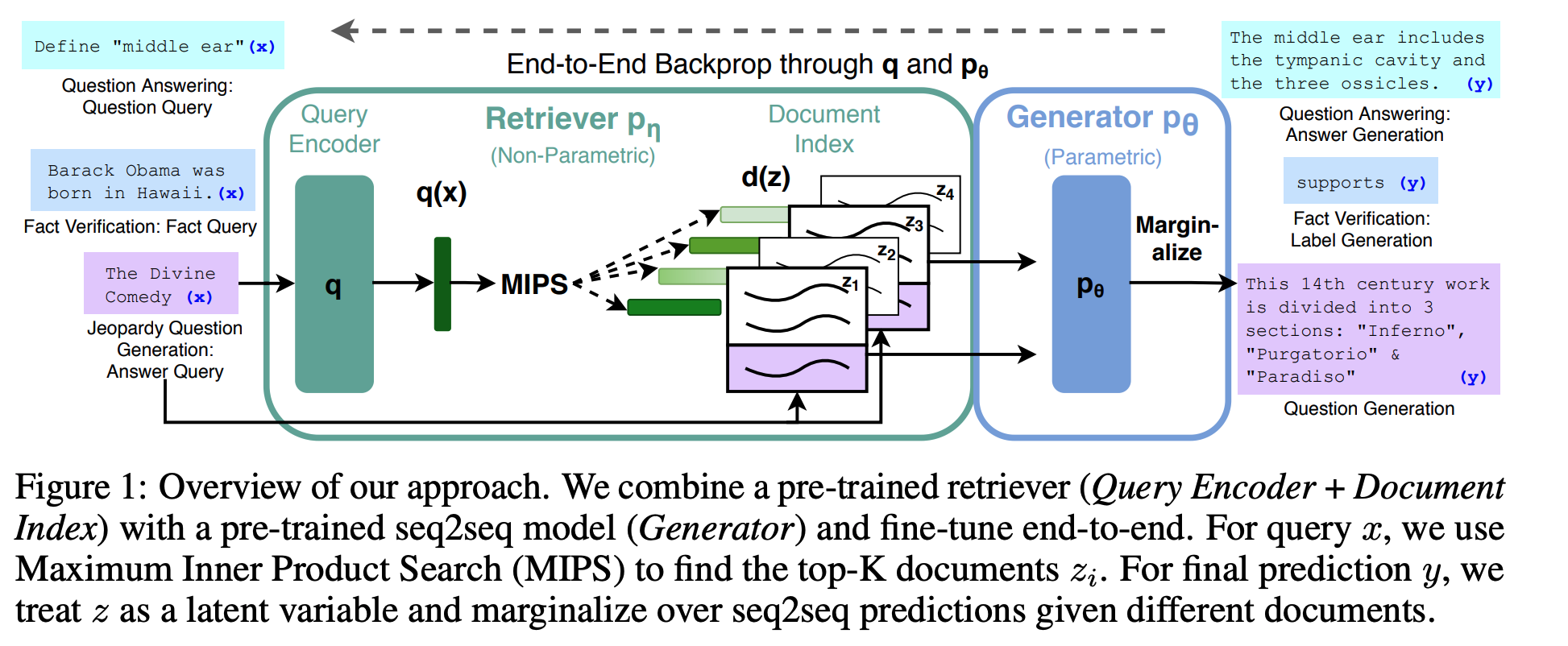

The concept of the RAG model was proposed in the paper Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks (2020, Patrick Lewis et al), which combines the strengths of parametric and non-parametric memory. The RAG model is composed of two components: a retriever and a generator, and the whole pipeline is trained end-to-end.

The retriever is responsible for fetching relevant facts from external sources, while the generator is responsible for generating text based on the retrieved facts. The paper was published before the release of ChatGPT, and due to the in-context learning ability of LLMs, there is no need to train the RAG model for LLM end-to-end. The information retrieved by the retriever can be directly fed into the generator to generate the text. (During the LLM fine-tuning stage, the RAG model can be tuned end-to-end to enhance performance).

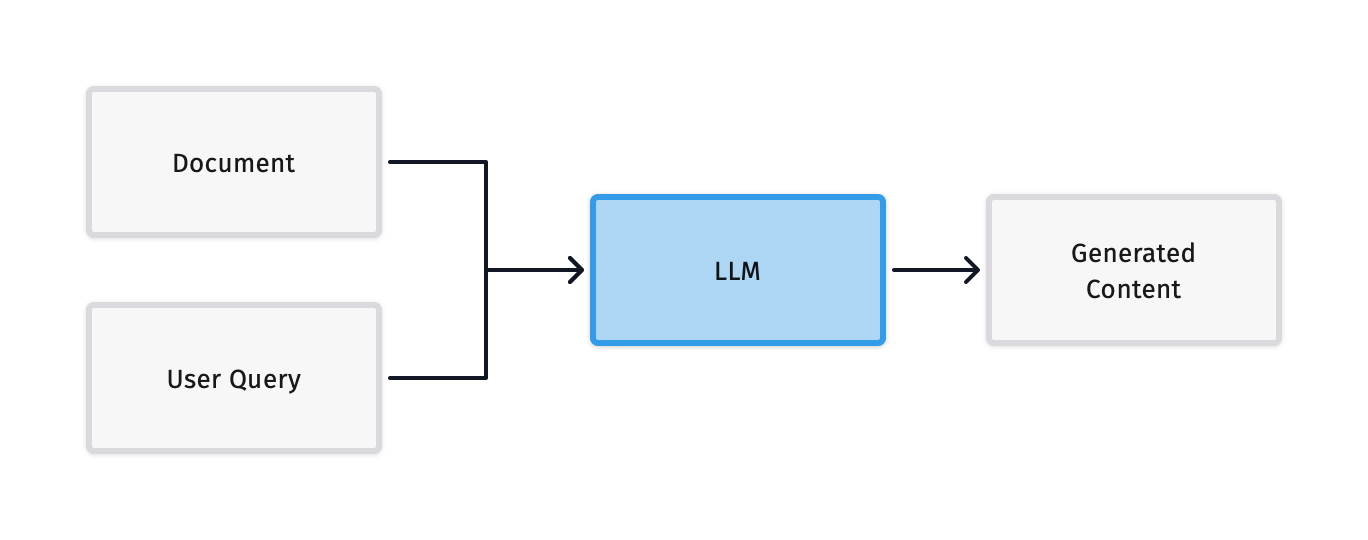

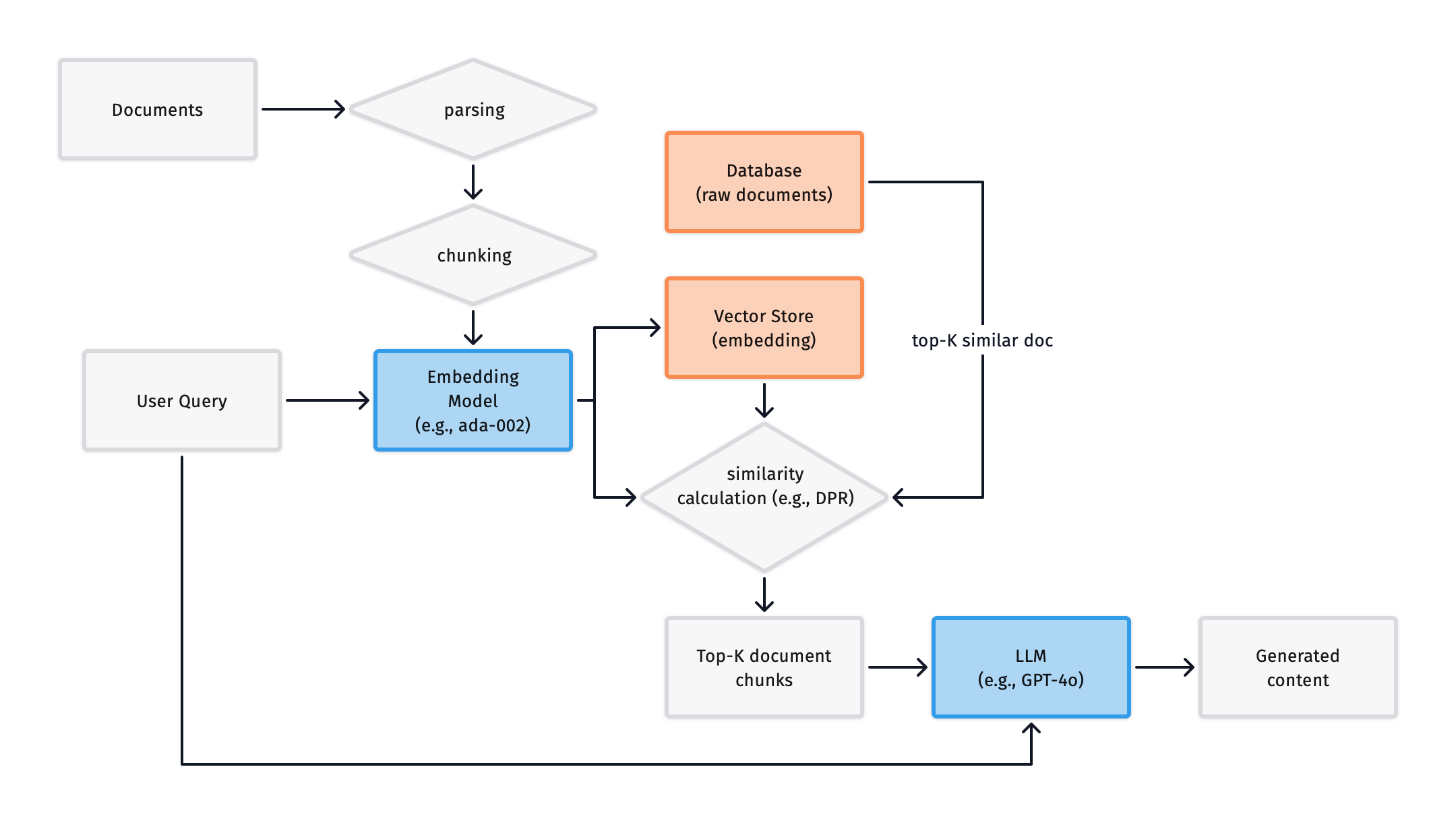

Using the in-context learning capability of LLMs, we can design a simple RAG system as shown below:

This system simply combines external information with the user query and inputs it into the LLM to generate a more accurate response. However, this system also has some obvious drawbacks:

- Unable to handle large amounts of external information: Due to the context window length limitations of Transformer models, inputting a large amount of information can lead to memory issues and information redundancy.

- Unable to filter information based on the user query: Since the information is directly input into the LLM, it cannot specifically retrieve relevant information based on the user query, leading to potentially inaccurate responses.

Next, we will introduce how to optimize the RAG model to address the above issues.

Vector Database

In practical applications of the RAG model, we often need to use a vector database to store external information. This vector database can be a simple key-value database or a more complex graph database.

Let’s take the upsert API of ChromaDB as an example:

collection.upsert(

documents=[

"This is a document about pineapple",

"This is a document about oranges"

],

ids=["id1", "id2"]

)

Here, documents is a list containing two documents, and ids are the IDs of these two documents.

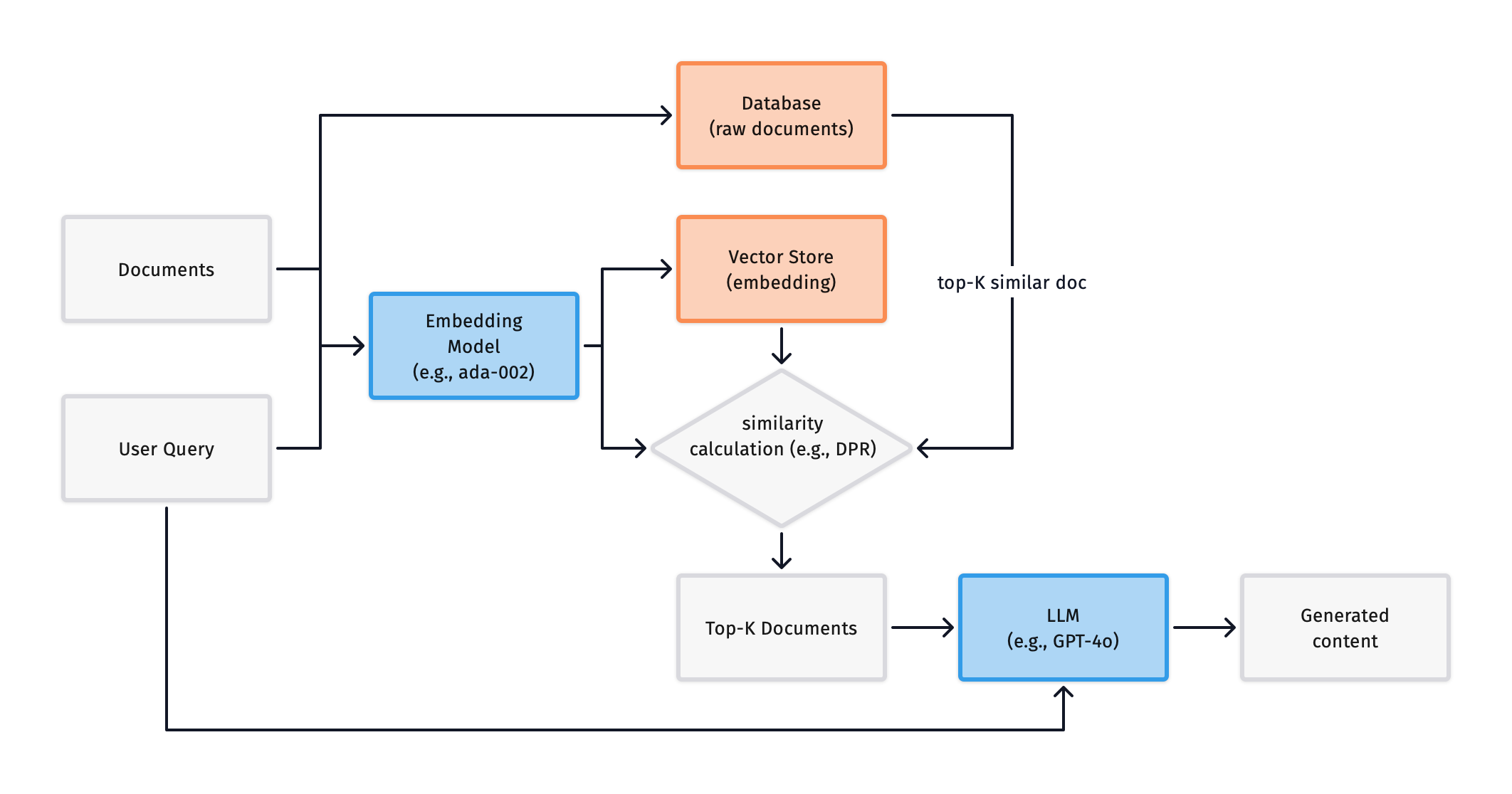

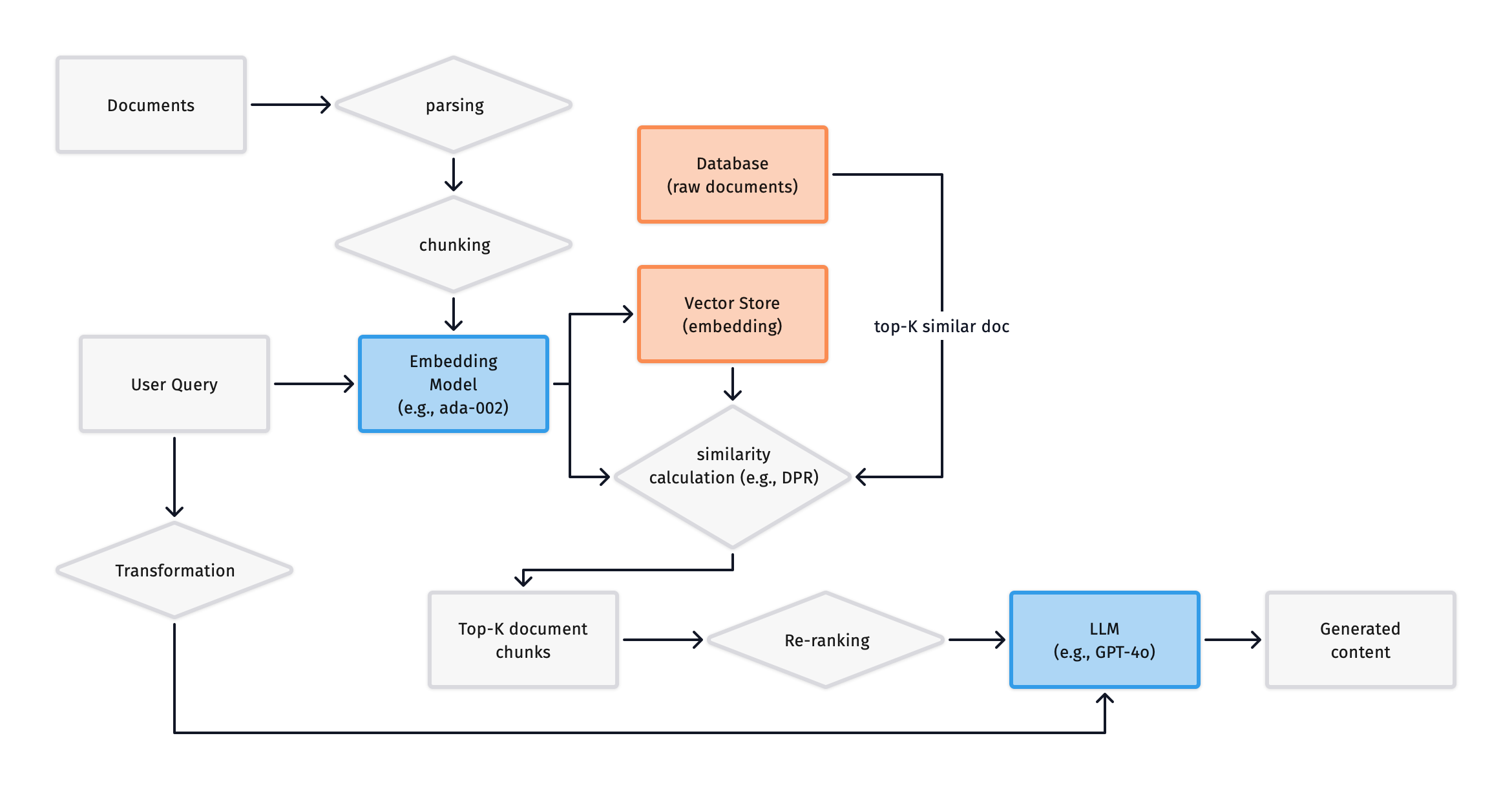

Based on such an API, we can also design and add a simple vector database to the above RAG pipeline, as shown below:

In this system, the original document data is stored in the Database, while the corresponding embeddings are stored in the Vector Store. Documents are converted into embeddings by the Embedding Model and stored in advance. When a query is made, the query is converted into an embedding by the Embedding Model and compared with all embeddings in the Vector Store to calculate similarity (Vladimir Karpukhin et al, 2020), returning the most similar documents.

Additionally, a Vector Index between the Database and Vector Store contains the mapping between document IDs and embeddings. For large-scale text retrieval, we can use libraries like FAISS, nmslib, or Annoy.

In summary, the introduction of a vector database solves the second issue mentioned above: the system can specifically search for information based on the user query. However, when dealing with an excessive amount of text, it is unreasonable to input an overly long text as a single vector into the LLM, so further optimization of the system is needed.

Chunking

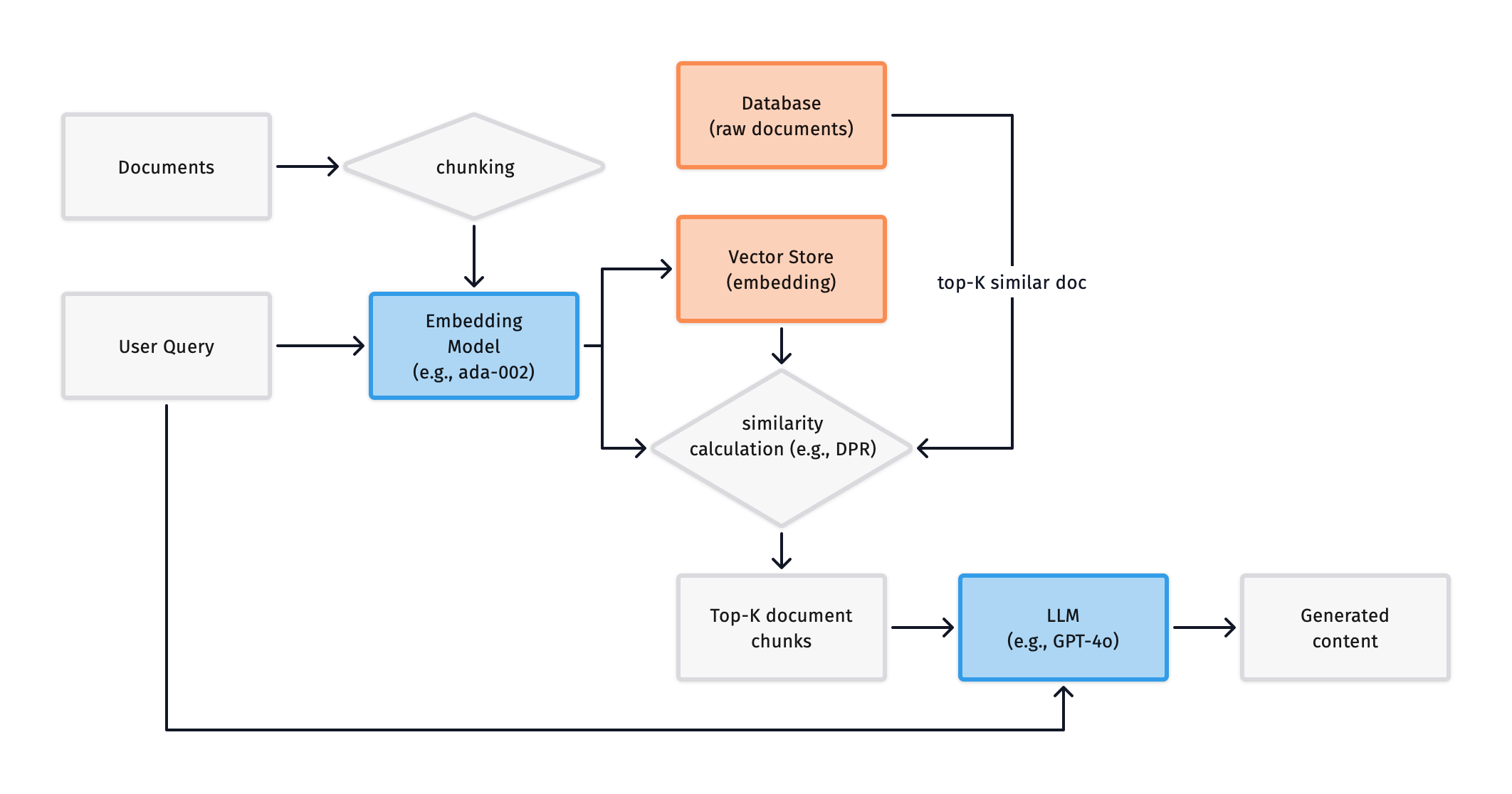

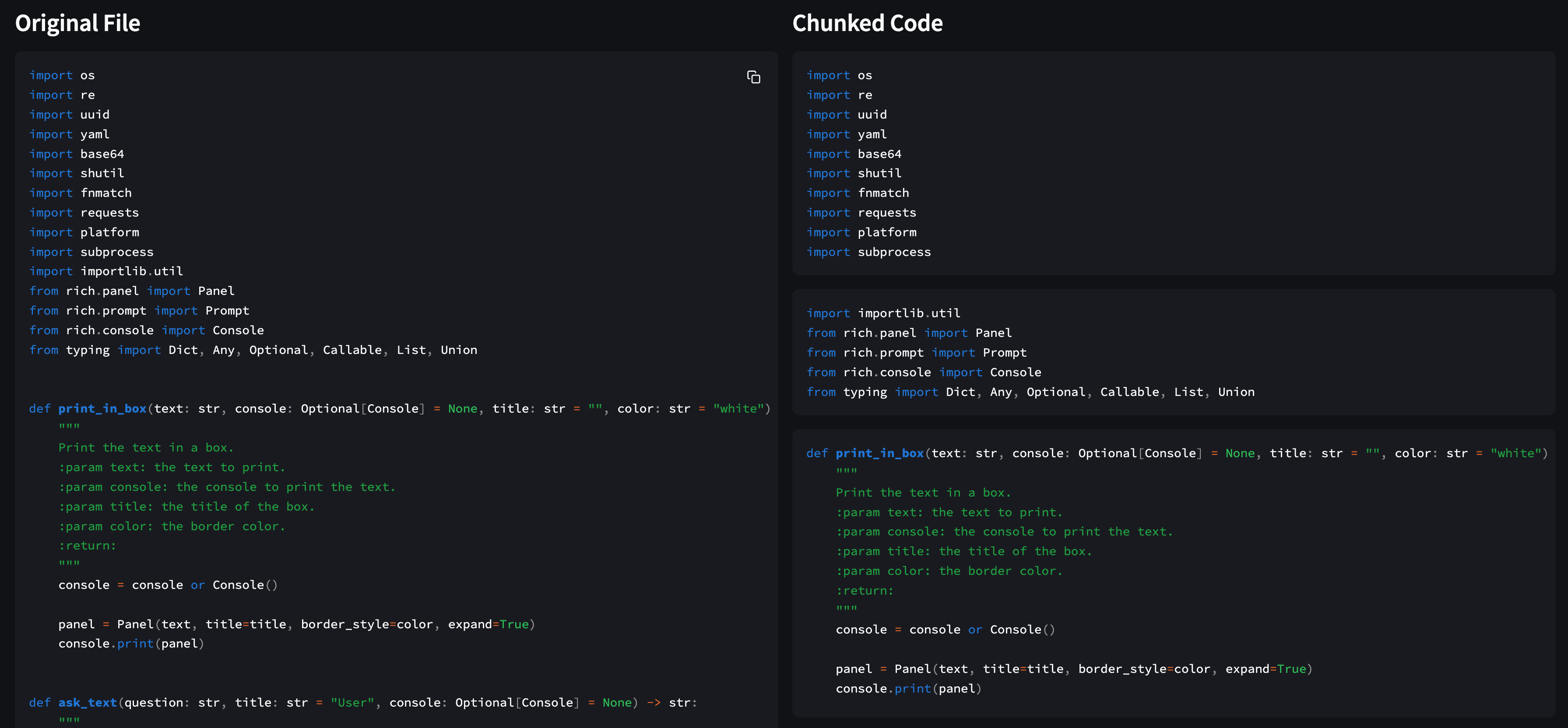

To solve the problem of long input text, we can split the text into chunks and store each chunk separately in the vector database, as shown below:

We process the document by splitting it into chunks before inputting it, solving the problem of excessive input length. However, this design also introduces a new issue: the relationships between chunks may be lost, leading to inaccurate responses. For example, if an article is split into two chunks, during response generation, we might generate two unrelated responses—because splitting chunks too crudely may separate a complete sentence into two “incoherent” segments, leading to LLM hallucinations.

The choice of chunk size becomes crucial in this context. On the one hand, we want the chunk size to be as large as possible to minimize loss of relationships between chunks; on the other hand, we want the chunk size to be as small as possible to reduce system load and adapt to models with context window limitations.

Dynamic Chunk Size

This is a more flexible chunking approach where we dynamically adjust the chunk size based on semantics. For example, if we need to split a code file, we should dynamically adjust the chunk size based on the semantics of the code, such as treating a function as a chunk or an if-else statement as a chunk. These chunks may have different sizes, so we need to design a max_chunk_size to ensure system stability.

For text data, paragraph-based chunking can be adopted, treating each paragraph (or chapter) as a chunk. Under stable system conditions, we can set a relatively large chunk size.

Thus, we can add a parsing module to the system to preprocess the text (semantically segment it) before chunking, as shown below:

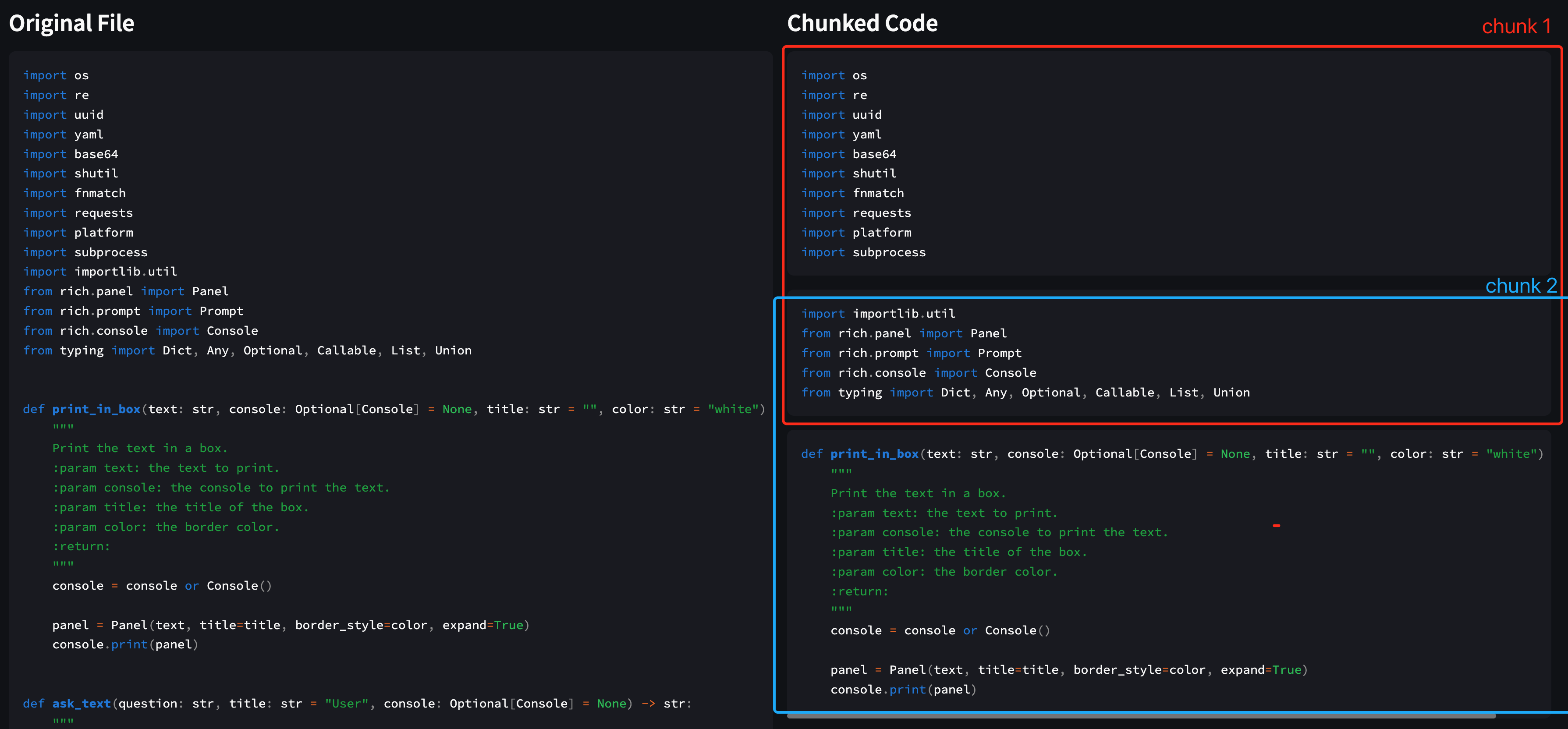

The above code RAG system, after processing by the parser, can obtain semantically related chunks, as shown:

Chunk Overlap

To address the problem of loss of relationships between chunks, we can introduce the concept of chunk overlap, where there is some overlap of information between chunks. As shown:

The downside of this approach is that more chunks are needed to store the same amount of document, resulting in additional storage overhead.

Context Enrichment

The loss of information between chunks can also be addressed through context enrichment. During response generation, we can expand the existing chunk to include more relevant information within the context window without compromising retrieval efficiency. For example, when constructing a code RAG system, we can perform dynamic chunking of code to retain semantic information, but each chunk may vary in size. This is suboptimal for data storage, but through context enrichment, we can expand all chunks to max_chunk_size, ensuring that all chunks have a uniform size while introducing chunk overlaps.

Taking the Code RAG example mentioned earlier:

We enriched the context of chunks to ensure no loss of information between code blocks while maintaining consistent chunk sizes (red and blue boxes).

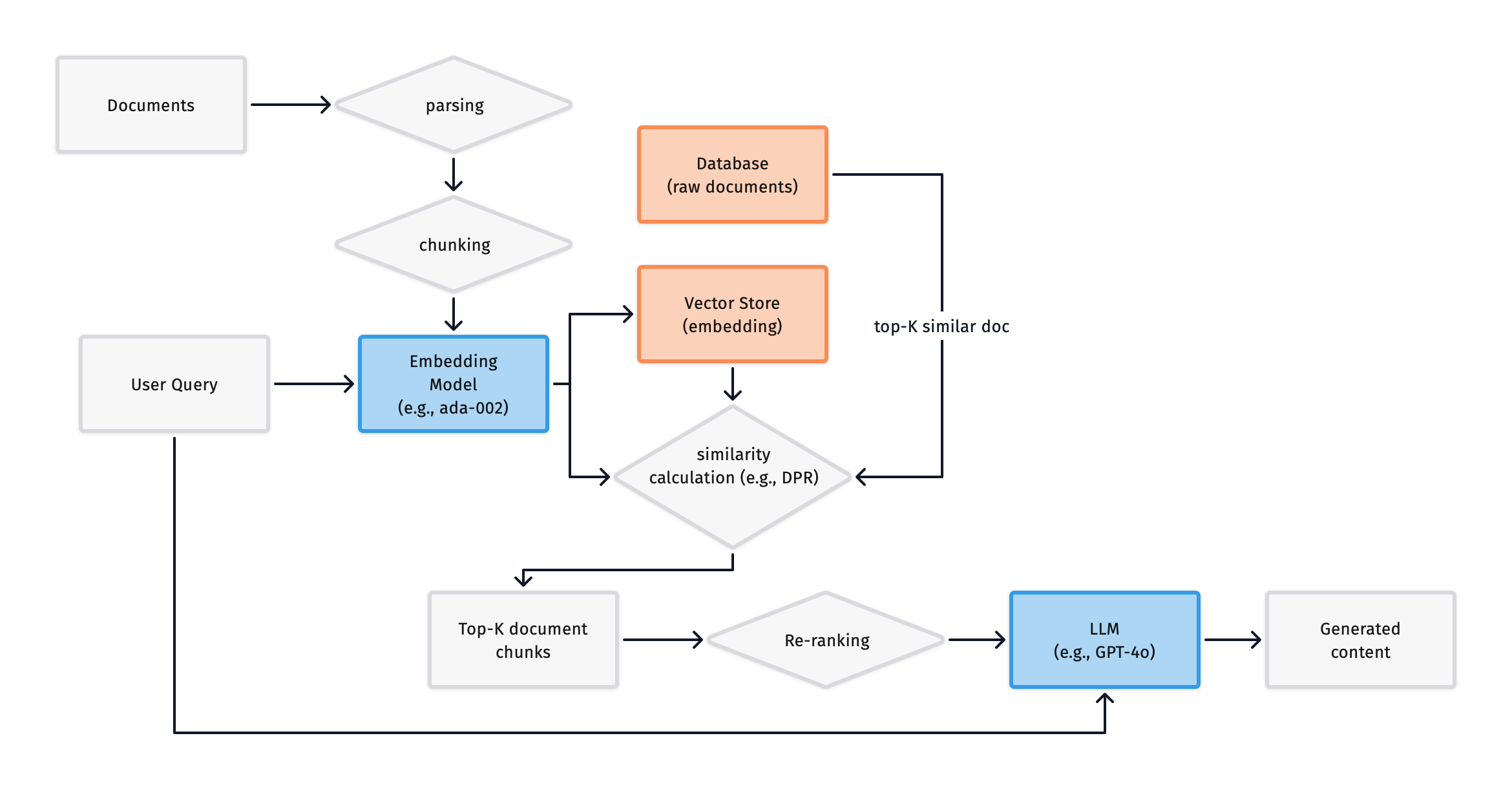

Re-ranking

We call it Re-ranking because we introduce a new Ranker module here, whose purpose is to re-order the results returned by the Retriever to ensure that the most relevant information is input into the LLM. As shown below:

The principle is straightforward: since the retriever in a RAG model matches based on vector similarity, the match may be “most relevant” but not necessarily “most useful”. So how do we re-order it?

Agent-based Re-ranking

We can use another model for ranking. This model could be a smaller one or an LLM-based agent. Its task is to determine which documents are most useful and then input those into the LLM. This design ensures that the most useful information is input into the LLM but also introduces additional complexity, as we need an extra model for ranking.

Graph-based Re-ranking

We can use a graph model for ranking. A knowledge graph can compute the intrinsic relationships between chunks, extract entities, and understand the text from a high-level perspective. For some high-level tasks (e.g., summarization), graph-based re-ranking is an excellent choice.

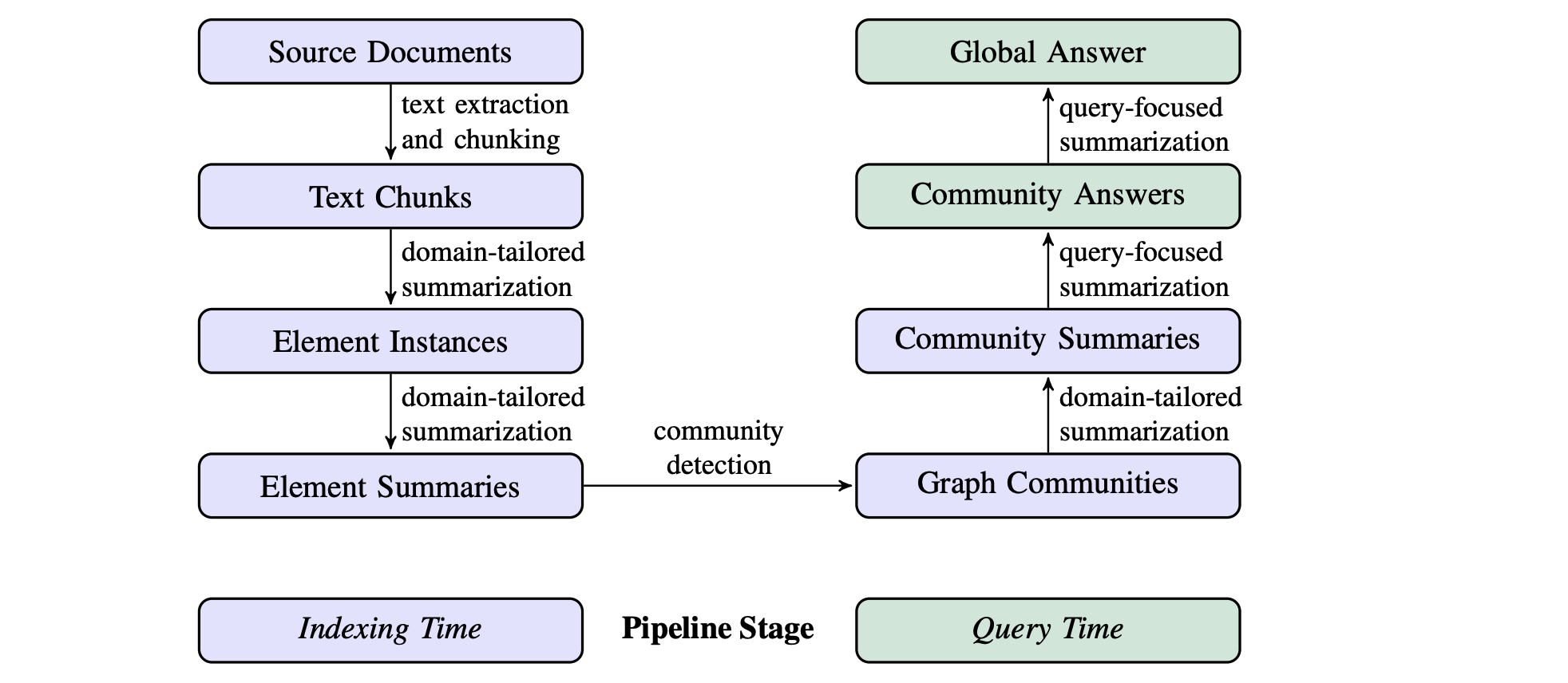

GraphRAG (Darren Edge et al, 2024) proposed enhancing RAG using graphs, as shown below:

For retrieved text chunks:

- Construct a graph: Model the entities and relationships in the text into a knowledge graph.

- Community detection and summary generation: Use community detection algorithms (e.g., Leiden) to partition the graph into a set of closely related entity communities. LLM then generates summaries for these communities, providing a descriptive summary for each community.

- Query processing and final answer generation: For the user query, each community’s summary is used to generate part of the response, and these parts are then summarized into a final answer.

This method supports answering global awareness questions for datasets and large-scale texts, especially when the data scale exceeds millions of tokens.

Hypothetical Questions/HyDE

To better match the retrieved chunks with the user’s query, we can generate “questions” for each chunk. This design is intuitive because, in question-answer paired datasets, matching the question with the user’s query is more in line with human thought processes. We then rank the chunks based on question similarity to ensure that “useful” data is given higher priority. HyDE works in the opposite way—it generates hypothetical answers for each query and then ranks the chunks based on the similarity between these answers and the chunks. We can view HyDE as a method for query transformation (which we will introduce shortly).

Fusion Retrieval

This is another common re-ranking method. We can use both embedding similarity calculation and keyword-based search methods (e.g., BM25) to rank results. The results of both methods are fused to enhance retrieval effectiveness.

Query Transformation

Apart from post-processing, we can also process the query beforehand to ensure more accurate information retrieval. As shown below:

We added a Transformation module, and now let’s discuss some specific methods:

Multi-Step Query Transformations

The multi-step query transformation approach splits the user’s query into sequential subquestions. This method can be handy when working with complex questions. For example, if the user asks a question like “Are there any good restaurants near me?”, the system can split the question into two subquestions:

- “What are the good restaurants?”

- “Are there any restaurants near me?”.

The information retrieved from the database can then be used to answer these subquestions, and the final answer can be generated by combining the results.

Query Rewriting

Query rewriting is another method that can be used to improve the accuracy of information retrieval. In this approach, the system rewrites the user’s query to make it more specific or relevant to the information stored in the database. For example, if the user asks a question like “What are the best pizza places in New York?”, the system can rewrite the query to “What are the best Italian restaurants in New York?” to make it more specific. This can help the system retrieve more accurate information from the database.

Query Expansion

By expanding the query, we can broaden the match for retrieval information. The principle is to expand the query using synonyms or similar words to increase the amount of information retrieved. The advantage of this method is its simplicity, but it also has some drawbacks: the expanded query may introduce noise, leading to inaccurate retrieval.

An example question of query expansion: “What is the most colorful bird in the world?” can be expanded to “What is the most colorful bird in the world? (e.g., parrot, peacock)”, where some examples of colorful birds are provided.

Query Routing

This is suitable for complex scenarios involving multiple databases. We need to route the query to the appropriate database for retrieval. One example is multimodal RAG, where we need to send image queries to an image database and text queries to a text database, then fuse the retrieval results before inputting them into the LLM. Image data requires additional models to compute embeddings, which are then matched with text data.