Java Memory Visibility - Volatile

Table of Contents

- Java Memory Model and Visibility

- Instruction Reordering

- Ensuring Visibility with the

volatileKeyword - Ensuring Visibility with the

synchronizedKeyword - Similarities and Differences Between

synchronizedandvolatileKeywords

Java Memory Model and Visibility

We know that the synchronized keyword essentially functions as a mutex lock, ensuring the order of execution and synchronization between different threads in a program. When it comes to variables in a Java program across different threads, there’s a crucial property to understand: visibility.

So, what is visibility?

Before grasping the concept of visibility, we need to briefly understand the Java Memory Model (JMM). The Java Memory Model is essentially a specification used by Java to manage memory. It describes the access rules for various variables (shared variables between threads) in Java programs, as well as the underlying details of storing variables in memory and reading variables from memory within the JVM. For Java threads, the memory is mainly divided into two types:

- Main Memory: Corresponds mainly to the data portion of object instances in the Java heap.

- Thread Working Memory (Local Memory): Corresponds to certain areas in the JVM stack. It’s an abstract concept in the JMM and doesn’t physically exist.

When understanding these two types of memory, I often wanted to compare them to the previously mentioned heap and stack memory. However, in reality, main memory and working memory don’t have a direct connection with heap and stack memory.

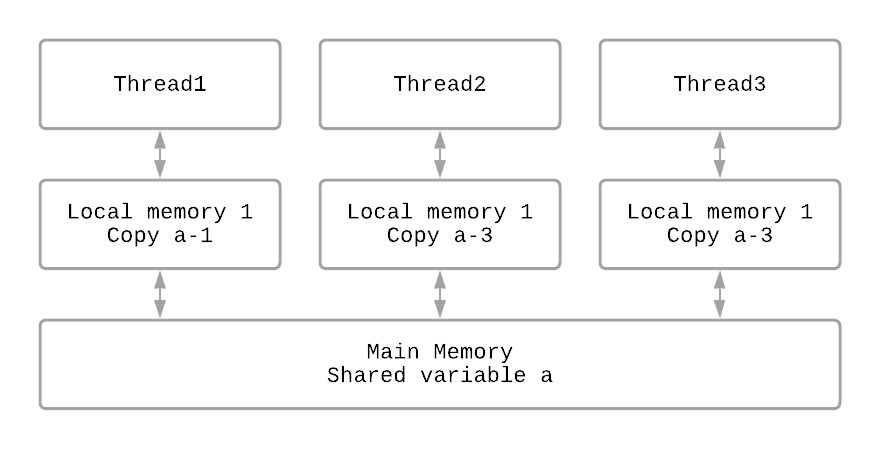

Back to the main topic, we can use a simple abstract diagram to understand the Java Memory Model:

From the diagram above, we can see that assuming there are three threads: Thread1, Thread2, and Thread3. During their execution, they all perform some operations on the variable a. These operations are based on the regulations provided by the JMM:

- All variables are stored in main memory.

- Each thread has its own independent working memory, which stores copies of the variables used by that thread (a copy of the variable from main memory).

- All operations on shared variables by a thread must be performed in its own working memory; it cannot read or write directly from main memory.

- Threads cannot directly access variables in the working memory of other threads; the transfer of variable values between threads must be done through main memory.

In other words, if a thread wants to operate on variable a, it must first obtain a copy of a from main memory, then modify this copy in its own local memory (working memory). After the modification is complete, the “new version of a” in the local memory is updated back to main memory.

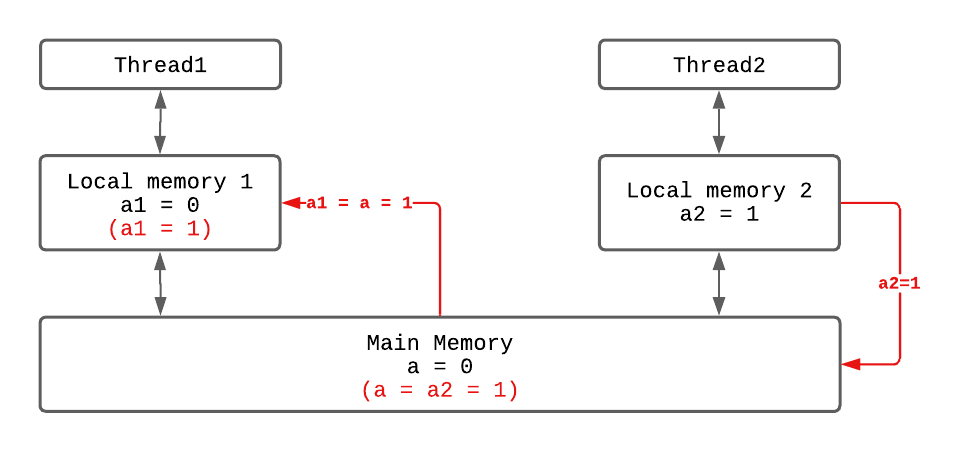

After explaining all this, how does it relate to visibility? Let’s look at the diagram below:

In the diagram, initially, both Thread1 and Thread2 obtain a copy of the shared variable a from main memory: a1 and a2, with initial values satisfying a1 = a2 = a = 0. As thread operations proceed, Thread2 changes the value of a2 to 1. Due to the invisibility between threads, a1 and a2 end up with inconsistent values. To solve this problem, Thread2 needs to synchronize its modified a2 back to main memory (as shown by the red arrow), and then refresh it to Thread1 through main memory. This is how the Java Memory Model synchronizes variables between threads.

In summary, visibility means that in different threads, a modification to the value of a shared variable by one thread can be promptly seen by other threads. For Thread1’s modification to the shared variable to be promptly seen by Thread2, the following two steps must occur:

-

- Flush the updated shared variable in Working Memory 1 back to main memory.

-

- Update the latest value of the shared variable from main memory to Working Memory 2.

Instruction Reordering

In a multithreaded environment, besides the invisibility caused by each thread’s local working memory, instruction reordering can also affect the semantics and results of inter-thread execution to some extent. So, what is reordering?

There’s an old saying, “What you see is what you get,” but in computer program execution, that’s not the case. To improve program performance, compilers or processors may optimize the execution order of programs, making the actual execution sequence different from the code’s written sequence.

// written sequence

int B = 2; // 1

int A = 1; // 2

int C = A + B; // 3

// actual execution sequence

int A = 1; // 1

int B = 2; // 2

int C = A + B; // 3

Program reordering can be divided into the following categories:

- Compiler Optimizations (Compiler Reordering)

- Instruction-Level Parallelism (Processor Reordering)

- Memory System Reordering (Processor Reordering)

Although code execution may not follow the written sequence, to ensure that the final output of single-threaded code isn’t changed due to instruction reordering, compilers, runtime environments, and processors adhere to certain specifications, mainly the as-if-serial semantics and the program order rule of happens-before.

As-if-serial Semantics: No matter how reordering is done (by compilers and processors to improve parallelism), the execution result of a (single-threaded) program cannot be changed.

To comply with the as-if-serial semantics, compilers and processors won’t reorder operations that have data dependencies, because such reordering would change the execution result. However, if operations have no data dependencies, they may be reordered by the compiler and processor. To illustrate this, let’s continue using the example above:

int A = 1; // 1

int B = 2; // 2

int C = A + B; // 3

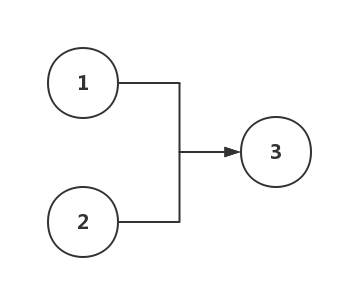

In this code, there are no data dependencies between the execution results of the first and second lines because the successful execution of the first and second lines doesn’t rely on each other’s results. However, the calculation of C in the third line depends on A and B. This dependency can be represented by the following diagram:

Therefore, based on the dependency, the as-if-serial semantics will allow the first and second lines of the program to be reordered, but the execution of the third line must occur after the first two lines. The as-if-serial semantics protect single-threaded programs. Compilers, runtime environments, and processors that comply with the as-if-serial semantics create an illusion for single-threaded programmers: the program is executed in the order it’s written. The as-if-serial semantics mean that single-threaded programmers don’t need to worry about reordering interfering with them or about memory visibility issues.

However, in a multithreaded context, it’s not that simple. Instruction reordering may lead to different results when threads working concurrently execute the same program. To illustrate this, let’s look at the following small program:

public class Test {

int count = 0;

boolean running = false;

public void write() {

count = 1; // 1

running = true; // 2

}

public void read() {

if (running) { // 3

int result = count++; // 4

}

}

}

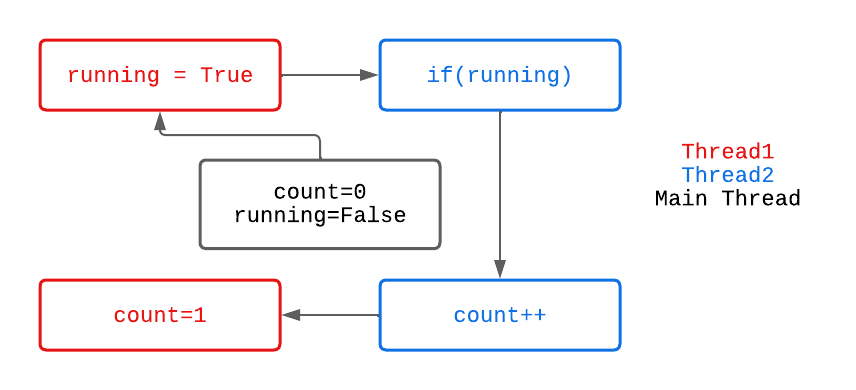

Here, we define a boolean flag running to indicate whether the value of count has been written. Suppose we have two threads (Thread1 and Thread2), where Thread1 first executes write() to write to the variable count, and then Thread2 executes the read() method. When Thread2 runs to the fourth line, can it see the write operation of count performed by Thread1?

The answer is: not necessarily.

Analyzing write(), statements 1 and 2 actually have no data dependency. According to the as-if-serial semantics, these two lines may be reordered during actual execution. Similarly, for the read() method, if(running) and int result = count++; also have no data dependency and may be reordered. For Thread1 and Thread2, when statements 1 and 2 are reordered, the program execution might appear as follows:

In this case, the count++ statement in Thread2 is executed before count = 1 in Thread1. Compared to before reordering, the final value of count becomes 1 instead of 2. Thus, reordering in a multithreaded environment disrupts the original semantics. Similarly, for statements 3 and 4, you can analyze whether reordering would lead to thread safety issues (first consider data dependencies and control flow dependencies).

Ensuring Visibility with the volatile Keyword

To solve the issue of variable visibility in the Java Memory Model for multithreaded variables, as mentioned in the previous article, we can use the mutex lock feature of synchronized to ensure variable visibility between threads.

However, as previously mentioned, the synchronized keyword is essentially a heavyweight lock. To optimize in such cases, we can use the volatile keyword. The volatile keyword can modify variables, and a variable modified by it will have the following characteristics:

- Ensures visibility when different threads operate on this variable (a new value written by one thread is immediately visible to other threads).

- Prohibits instruction reordering.

When writing to a volatile variable, the JMM will flush the shared variable in the local memory corresponding to that thread back to main memory. Additionally, when reading a volatile variable, the JMM will invalidate the local memory corresponding to that thread, and the thread will then read the shared variable from main memory. This is why the volatile keyword can ensure visibility of the same variable across different threads.

As for the underlying implementation of volatile, I won’t delve deeply, but we can briefly understand: if we generate assembly code for code with and without the volatile keyword, we’ll find that the code with the volatile keyword has an extra lock prefix instruction.

What does this lock prefix instruction do?

- Prevents subsequent instructions from being reordered before the memory barrier during reordering.

- Forces the CPU’s cache to be written to memory.

- The write action also invalidates the caches of other CPUs or cores, making the new written value visible to other threads.

With all that said, using volatile is actually quite simple. Let’s look at a demo:

public class VolatileUse {

private volatile boolean running = true; // Compare the results with and without the volatile keyword.

void m() {

System.out.println("m start...");

while (running) {

}

System.out.println("m end...");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

VolatileUse t = new VolatileUse();

new Thread(t::m, "t1").start();

try {

TimeUnit.SECONDS.sleep(1);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

t.running = false;

}

}

In this small program, if we add the volatile keyword to running, the operation t.running = false; in the main thread will be seen by thread t, breaking the infinite loop and allowing the method m() to end normally. If we don’t add the keyword, the program will be stuck in the infinite loop of method m(), and will never output m end....

So, can the volatile keyword replace synchronized? Let’s look at another demo:

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

/**

* The volatile keyword makes a variable visible among multiple threads.

* Volatile only ensures visibility; synchronized ensures both visibility and atomicity but is less efficient than volatile.

*

* @author huangyz0918

*/

public class VolatileUse02 {

volatile int count = 0;

void m() {

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

count++;

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

VolatileUse02 t = new VolatileUse02();

List<Thread> threads = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

threads.add(new Thread(t::m, "thread-" + i));

}

threads.forEach((o) -> o.start());

threads.forEach((o) -> {

try {

o.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

});

System.out.println(t.count);

}

}

Let’s try running it:

94141

Run it again:

97096

We can see that the results are different each time, and none reach the expected theoretical value of 100,000. Why is this? (The count++ statement includes reading the value of count, incrementing it, and reassigning it.)

We can understand it this way: Two threads (Thread A and Thread B) are both performing increment operations on the variable count. At a certain moment, Thread A reads the value of count as 100. At this point, it’s blocked. Since it hasn’t modified the variable, the volatile rule isn’t triggered.

Thread B also reads the value of count. The value in main memory is still 100. It increments it and immediately writes it back to main memory, making it 101. It’s then Thread A’s turn to execute. Since its working memory holds the value 100, it continues to increment and writes back to main memory, overwriting 101 with 101 again. So, although both threads performed two increment operations, the result only increased by one.

Some might say, doesn’t volatile invalidate cache lines? But here, from the time Thread A starts reading the value of count until Thread B also operates, the value of count hasn’t been modified, so when Thread B reads it, it’s still 100.

Others might say, when Thread B writes 101 back to main memory, won’t it invalidate Thread A’s cache? But Thread A has already performed the read operation. Only when performing a read operation and finding its cache line invalid will it read the value from main memory. So here, Thread A continues with its increment.

In summary, volatile cannot completely replace the synchronized keyword because, in some complex business logic, volatile cannot ensure complete synchronization and atomicity of operations between multiple threads.

Ensuring Visibility with the synchronized Keyword

So, why does the synchronized keyword ensure visibility?

In the Java Memory Model, there are two rules regarding the synchronized keyword:

- Before a thread releases a lock, it must flush the latest value of the shared variable to main memory.

- Before a thread acquires a lock, it will invalidate the shared variable in its working memory, so when using the shared variable, it needs to read the latest value from main memory (Note: acquiring and releasing the lock need to be the same lock).

These two rules ensure that the modifications to shared variables before a thread releases the lock are visible to other threads when they acquire the same lock next time, thereby achieving visibility. Let’s look at the specific implementation steps before and after acquiring the synchronized lock:

- Acquire the mutex lock.

- Clear the working memory.

- Copy the latest version of the variables from main memory to working memory.

- Execute the code.

- Flush the updated values of the shared variables back to main memory.

- Release the mutex lock.

The steps ensuring visibility are evident.

Similarities and Differences Between synchronized and volatile Keywords

Finally, let’s discuss the similarities and differences between these two keywords, which are popular topics in interviews at many internet companies.

A brief summary:

volatiledoesn’t require locking; it’s more lightweight thansynchronizedand doesn’t block threads.- From the perspective of memory visibility, a

volatileread is similar to acquiring a lock, and avolatilewrite is similar to releasing a lock. synchronizedensures both visibility and atomicity, whilevolatileonly ensures visibility and cannot guarantee atomicity.volatilecan only modify variables, whereassynchronizedcan also modify methods.